Some years ago, I was handed a copy of a souvenir booklet of an unusual event. The year was 1918 and before the hostilities of the First World War had officially ceased. Confidence was high, it was a brave new world.

This invitation was made out to my great-aunt, Ruby Thirza May Fursdon who was born and grew up in Devon. She was 22 years old at the time.

Note that it required a very early start, only about an hour after sunrise, and breakfast was scheduled just half an hour after the launch was due! They did not expect anything to go wrong, which sadly turned out not to be the case.

I reproduce the booklet here as originally published except that I have added several intermediate paragraph breaks and headings. The original was very heavy on text! It is interesting as a piece of social history and it also shows how writing and punctuation standards have changed over the years.

|

“Build me straight O worthy Master, Staunch and strong, a goodly vessel, That shall laugh at all disaster, And with wave and whirlwind wrestle!” And with a voice that was full of glee He answered, “Ere long we will launch A vessel as goodly, and strong and staunch, As ever weathered a wintry sea.” Loud and sudden there was heard, All around them and below, The sound of hammers, blow on blow, Knocking away the shores and spurs, And see, she stirs! She starts, she moves, she seems to feel The thrill of life along her keel, And, spurning with her foot the ground, |

With one exulting, joyous bound, She leaps into the ocean’s arms! Thou, too, sail on, O ship of State! Sail on, O Union, strong and great! Humanity, with all its fears, With all the hopes of future years, Is hanging breathless on thy fate! In spite of rock and tempest’s roar, In spite of false lights on the shore, Sail on, nor fear to breast the sea, Our hearts, our hopes, are all with thee. Our hearts, our hopes, our prayers, our tears. Our faith triumphant o’er our fears. Are all with thee – are all with thee! Longfellow “The building of the Ship.” 1850. |

BARNSTAPLE (or Barum), the Metropolis of North Devon, charmingly situated on the banks of the river Taw, is not only an enterprising and progressive township, but is full of interest for the historical student and the lover of antiquities. Barnstaple ranks among the oldest boroughs in the Kingdom : indeed, there is strong evidence to support the claim that it is absolutely the oldest. The town is the centre of a network of ancient British, Roman and Saxon roads, a sufficient indication alike of its high antiquity and its importance in the early days of English history. Barnstaple appeared in the list of Wessex burghs in 900, and from its position as a Royal fortress or burgh came privileges which were confirmed in the Middle Ages. Athelstan, the traditional founder of The Castle (the Mound of which remains), was 500 years ago claimed as the author of the town’s representative rights. The Corporation proper dates from Philip and Mary, a Charter issued in 1556 constituting the Corporation. But the town had sustained its prescriptive right to a Mayor centuries before. A Charter of Henry II confirms one of Henry I (between 1100 and 1135) under which Barnstaple had the same customs and privileges as London, one of which was to elect a Chief Magistrate (or Mayor). Barnstaple had its own Mint a thousand years ago. The borough returned Members to Parliament without a break from the time of Edward I to 1885, when Barnstaple was merged in the extensive Parliamentary Division to which it gives its name.

The beginning of Barum’s association with shipping – and with shipbuilding – is lost in the mists of antiquity. Sailing up the Taw, the Danes made Barnstaple their point of disembarkation for one of their greatest raids, and the existence of a Danish mound at the termination of the navigable point led the late Mr. J.R. Chanter, the greatest authority on the historical records of the town, to consider that the Danes effected a settlement here. Mr. Chanter also thought that Barnstaple was the point of disembarkation of the second expedition of the sons of Harold to endeavour to recover their heritage from the Norman Conqueror. Barnstaple was certainly a port of importance early in the Fourteenth Century, for it was one of the places represented in the first Council of Shipping, or Naval Parliament, in 1344, when 44 ports were summoned to send men well acquainted with naval affairs to attend a council to advise the King, Edward III, who desired to be informed of the state of the navy and shipping in England. It is on record that the privilege of Barnstaple as one of the cinque ports, with the other cinque ports granted by Edward the Confessor, was confirmed by William the Conqueror and Queen Elizabeth. Barum is also frequently referred to in the subsidy and miscellaneous writs, of early date, preserved in the Record Office.

The first record of a Barnstaple ship (according to Cotton, author of “Barnstaple during the Civil War”) goes back to 1434, when the “Nicholas,” a ship of 40 tons, presumably bui1t in the town, sailed down the Taw having on board a number of pilgrims bound for a shrine on the north coast of Spain. The spirit of adventure and commercial enterprise which distinguished the spacious days of Queen Elizabeth found congenial soil in North Devon, and Barum seamen and merchants risked much and often reaped rich rewards. Barnstaple contributed a share, commensurate with its importance as a port, of ships to the fleet which destroyed the Spanish Armada in 1588. Wyot, the Town Clerk of that period, records in his invaluable diary that “Five ships went over the Bar to join Sir Francis Drake at Plymouth.” Doubtless Bideford and Appledore contributed to the contingent which went from North Devon to swell Drake’s fleet, but Mr. R.W. Cotton, who made a special study of Barum’s maritime record, inclined to the opinion that Barnstaple provided three ships and two victuallers, all probably built in the town. Mr. Cotton also established the fact that an additional Barnstaple ship, “The John,” joined Drake’s fleet with 65 men after the great engagement had been fought. A supposed Armada chest is, by the way, preserved at the North Devon Athenaeum.

Barnstaple played a prominent part in the colonising developments which marked the latter part of the Sixteenth and the beginning of the Seventeenth Century, and Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Richard Grenville found at Barnstaple ships and men for their colonising expeditions to North America. Barnstaple ships were among the first to visit Newfoundland, and for over a century close trading relations existed between this Colony and Barnstaple. The town was throughout the Seventeenth Century noted for its import and export Trade, and its merchant princes had their ships in all the seas. Although, by a strange oversight, the diarists and other chroniclers whose records have enabled historians to picture the Barnstaple of this palmy period, make no mention of the existence of ship building yards – indeed, industry and commerce figure little in the old chronicles – it may be taken for granted that a goodly proportion, at all events, of the ships which did this pioneer work in colonization and commerce were built in yards at Barnstaple.

In the Sixteenth Century and the early part of the Seventeenth small vessels called “Pickards” were peculiar to the Bristol Channel, and Leland (who wrote early in the Sixteenth Century) said: “Pickards and other vessels come up by a gut out of the Haven to the bridge on the causey at Pilton town’s end” (Pilton being an adjunct of Barnstaple). This doubtless explained how it came to pass that in these early days (as well as in the early part of the Nineteenth Century) much of the ship building done at Barnstaple was carried out above the Long Bridge. In the same period Barum shipping owners and merchants often reaped a rich harvest by sending out reprisal ships under letters of marque. Thus in August, 1590 “The Prudence,” a ship of 100 tons belonging to Mr. Doddridge, of Barnstaple, sailed over the Bar on a reprisal voyage, and returned in December with a prize, “taken on the coast of Guinney, having in four chests gold to the value of sixteen thousand pounds and divers chains of gold, with civet and other things of great value.” No wonder that the diarist Town Clerk wrote: “Such a prize as this was never brought into port.” The chests and baskets of gold weighed 320 pounds! In January, 1592, “The Prudence” brought in another prize worth ten thousand pounds. This ship is described in an English Navy list of the period (1595) as “The Prudence, of Barnstaple, with 40 mariners and 70 soldiers, under the command of Captain Sir George Carew.”

From 1625-28, 15 owners of Barnstaple vessels were granted letters of marque, the tonnage ranging from 40 to 160 tons. Barnstaple ships were among the earliest to participate in the Newfoundland fisheries. In March, 1625, when, for State reasons, the departure of vessels from the outports was ordered to be stopped, the Mayor of Barnstaple reported to the Council that he had “stayed eleven ships bound for Newfoundland which had not set out, but some vessels were gone before the order arrived.”

During the Sixteenth Century there was considerable intercourse between Barnstaple and the French and Spanish ports, Barum’s woollen goods being the chief article of export. In 1590 eight ships are recorded as having sailed over the Bar for Rochelle. These fragmentary notes will at all events serve to show the antiquity and the importance of Barnstaple’s association with shipping – with all that shipping has meant in the development of Colonization and the building up of the greatest Empire the world has ever seen.

To come to actual shipbuilding, although there can be no doubt that the building of ships was a leading industry at Barnstaple for many centuries, precise details as to yards and builders cannot be supplied prior to about the middle of the Eighteenth Century. In 1770, Henry Lee was carrying on shipbuilding at Barnstaple, for there is an entry in one of the borough records that in that year he “received £20 from J. Hooper as an apprentice to be taught shipbuilding.” But Lee’s was one of several yards, for in 1773 the Mayor (Stewkly Stephens) was a shipbuilder, and in 1775 Thomas Wilkey had a shipbuilding yard at Litchdon Green (above the Long Bridge, and probably near the site of the present slipway at the entrance to the South Walk). The existence of a Shipwright’s Arms, an ancient inn, on the Square pointed to considerable employment in shipbuilding; in 1800 this inn was kept by Sebastian Hodge, and in 1838 by Thomas King.

Towards the close of the Eighteenth Century a famous Greenock shipbuilding firm became associated with Barnstaple, and in 1799 Wm. Scott, of Greenock, was married to Elizabeth, daughter of James Mallins, timber merchant, who rented the old Meeting-house of the Independents near North Walk. Timber suitable for shipbuilding was easily obtained in North Devon in these days, and for some years the Scotts built the hulls of ships at Barnstaple and sent them to their yards at Greenock to be fitted. This celebrated Greenock firm of to-day possesses an interesting mascot dating from its association with Barnstaple in Napoleonic days. It is a beautifu1ly-made model of the frigate “Melampus,” the work of French prisoners at Barnstaple in 1808 for “John Scott, shipbuilder, Greenock.” At the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, and at the time Queen Victoria ascended the Throne, shipbuilding formed an important industry at Barnstaple. In 1837 shipbuilding was carried on at four distinct yards – one at the end of Litchdon (just outside the Riversdale of to-day), anothcr at Pottington, another at the Pottington end of Rolle Quay, and the other at Pilton Quay (where Berry’s stores now stand). The chief yard was Westacott’s, situate in the early part of last century at the end of Litchdon. Four generations of Westacotts directed shipbuilding at Barnstaple in the Nineteenth Century, and it is a romantic coincidence that a member of this famous family of shipbuilders is responsible for the revival of this important industry in the ancient borough in the second decade of the Twentieth Century. Robert Westacott, who died in 1812, was a shipbuilder, and his two sons, William and John, were carrying on business in 1814, their yard being at Litchdon – this yard having prior to 1800 been conducted by John Wilkey. John Westacott was the proprietor when, some years prior to 1850, it was decided to remove the yard from Litchdon to the Bridge Wharf.

Prior to this change the scope of the shipbuilder at the Litchdon yard was strictly defined : no vessel could be built which could not pass through the arches of the Long Bridge. It was suggested at one time that two of the arches should be thrown into one, so that the arbitrary limit might be removed. But this was not allowed, and as there was a demand for larger vessels than had been produced at the old yard for centuries, Mr. John Westacott abandoned the site above the Bridge and established his yard on a convenient spot just below the Bridge (the site occupied to-day by Raleigh Cabinet Works). Shortly afterwards he was joined in the business by his son William, and the firm of Westacott and Son made rapid progress, establishing a very high reputation in the shipbuilding world. On the death of his father, Mr William Westacott succeeded to the business, and he continued the output of a very fine type of ship until 1885, when, mainly owing to the demand for iron and steel ships, the industry was allowed to lapse. Many other yards in different parts of the country shared a similar fate from the same cause. Building in the three other yards which existed in 1837 ceased many years before this, so that Westacott’s yard at Bridge Wharf was the last link with one of the most ancient industries in the borough. In the last few years of the building at Bridge Wharf Mr. William Westacott was assisted by his son John, who subsequently did shipbuilding on a considerable scale at Appledore. Mr. Percy Westacott, the head of the British Construction Co., which in this year of grace (1918) has started the building of reinforced concrete ships at Barnstaple, is the son of this Mr. John Westacott, and therefore a great-great-great-grandson of the Robert Westacott who started the family record of shipbuilding at Barnstaple towards the end of the Eighteenth Century.

After the removal of their shipbuilding operations to the Bridge Wharf, the Westacotts built many fine ships, and several are still in use. A notable launch was that in 1852 of the “Lady Ebrington,” built as an emigrant ship. Of 400 tons, she was one of several ships built on a model designed by Norman, of Liverpool. With George Harris as Captain she sailed from Barnstaple in August, 1852, taking a large number of North Devon emigrants to Australia. An illustration of this emigrant ship and a view of Westacott’s yard in 1870 are included in this souvenir. One of the largest vessels ever built at Barnstaple was the “Standard Bearer,” which was launched from Westacott’s yard in October, 1871. She was 156 feet long, with a tonnage of 640. She was christened by Miss Williams (now Mrs. Penn Curzon, of Watermouth Castle), daughter of Mr. C.H. Williams, who at that time represented the borough of Barnstaple in Parliament. About the same period the barque, “Red Cross Knight,” about 700 tons, built for a Swansea firm, was launched, and a barque exceeding 800 tons was launched from Westacott’s yard later. The last vessel built at this yard was the “Emma Louise,” a schooner belonging to a Braunton owner. In the early years of the reign of Queen Victoria ships were built at Barnstaple by Mr. John Goss (Pilton Quay and Rolle Quay) and Mr. Thorne (Pottington). In February, 1856, Miss Ballment (aged 12) christened at Rolle Quay a vessel built by her father, Mr. Hugh Ballment, a leading merchant, as well as shipbuilder, whose yard was by Rolle Quay, giving the vessel the combined names of her two brothers, “Robert and Alexander.” This daughter of Barum is now Lady Gould, wife of Sir Francis Carruthers Gould, the world-famous cartoonist, who is also a native of Barnstaple. The “Despatch,” the “Stranger,” and the “Swift,” vessels built at Pottington, are still in use.

As a corollary to shipbuilding, rope-making flourished at Barnstaple for centuries, but the industry survived the lapse of shipbuilding for a few years only. Perhaps the revival to-day of the more important industry may bring in its train the return of the “rope-walks” so dear to youth at Barnstaple in former generations. The revival may also serve, under Peace conditions, to secure the resuscitation of the Regattas which proved so popular with townspeople and visitors up to the time shipbuilding ceased at Barnstaple nearly forty years ago.

General View of the British Construction Co.’s Shipyard Branch, Barnstaple, from Sticklepath

So much by way of introduction to the story which is the raison d’etre of this souvenir. The advent of the steel age in shipbuilding caused the decline and ultimate abandonment of one of Barum’s most ancient industries. It is strange, but it is in accordance with poetic justice, that the advent of a rival to steel and iron in the realm of shipbuilding should be responsible, during the progress of the greatest war in history, for the revival of the shipbuilders’ activities at Barnstaple. It is, too quite a romance of industry that the gentleman responsible for the revival is a representative of the family – the Westacotts – which gave Barnstaple its distinction as a shipbuilding centre in the middle of last Century, Mr Percy Westacott, A.M. Inst. C.E., A.M.I. Mech. E., the head of the British Construction Co., being a grandson of the Mr. William Westacott who built the last wooden ship launched at Barnstaple. Last year, when ruthless U-boat warfare – conducted in defiance of International law – made the shipping situation serious, the advantages offered by the reinforced concrete system as applied to the production of vessels were pressed, and the Government authorities wisely decided to offer special inducements and facilities for the production of concrete ships, arrangements being made for the starting of many yards in different parts of the country. Mr. Percy Westacott, head of the British Construction Co. which has its chief offices at 39 Victoria Street, Westminster, S.W., was authorised by the Admiralty to start one of these yards, and his personal knowledge of the local conditions led him to establish the yard at Barnstaple. Practical business considerations, not sentiment, must decide such matters, but Mr. Westacott hopes that the revival of an ancient industry, in modernised form, may once more make Barnstaple a recognised shipbuilding centre and so prove a lasting benefit to the town. For industrial enterprise touches the life-springs of a community. As a matter of fact, Barnstaple is an ideal spot for such shipbuilding activities. The genia1 climate is favourable to work under exposed conditions, transport facilities by rail and water are excellent, there are ample facilities for power and lighting, there are no housing complications, and (to crown all) there are within easy reach inexhaustible deposits of the finest gravel procurable – gravel being a prime raw material of concrete.

At the beginning of the present year a splendid site was secured at the town end of Anchor Wood Bank, the site actually adjoining the spot where Westacott’s shipbuilding yard formerly stood. The foreshore and the land (situate between the old footpath to Anchor Wood and the Railway) which have been secured cover an area of 17 acres. Actual operations were started the last week in March. Since then marvels have been accomplished. The speed with which river-shore marshland was transformed into an up-to-date shipbuilding yard is deserving of the highest praise. Indeed, the Barnstaple Yard has beaten all records in this direction, as well as in the speed with which the first ship was got ready for launching. Seven slips have been provided for building vessels up to 1,500 tons, and in addition there are several berths for the construction of smaller barges. Between the first slip and the Bridge Wharf (Raleigh Cabinet) Works a massive river wall has been erected for the purposes of a fitting-out Wharf, where ships can be completely equipped. Four 1,000 ton barges and two tugs are at present on the slips. The Company contemplates extending the yard lower down the river, in order that ships of 10,000 tons dead weight may be built. Several acres of land contiguous to the Railway are devoted to carpenter’s shops, bending shops (where large and small steel bars, used for reinforcing the concrete, are bent by leverage with amazing ease), assembly shops, and mess-rooms and tea-rooms, trolley lines facilitating transport to the various sections. There are electric motors for mixing cement and electric power is also used for elevating the material to the distributing tower (which is 90 feet in height). For some time 500 men have been engaged at the yard, and it is hoped to double this number. Electric light and electric power are provided, and an electric welding plant is being installed.

The reinforced concrete ship has become a commercial fact owing to War exigencies, but there can be no doubt it has come to stay. Under War conditions the case for such ships is overwhelming. At a time when the conservation of iron and steel is all-important, the system saves something like 60 per cent. of steel. At a time when it is in the national interest that every pound should be made to go as far as possible, it saves about 30 per cent. in the cost of shipbuilding. Moreover, it permits of the use of a class of steel which is of no use to ordinary shipbuilders. Again, at a time when there is not enough skilled labour to go round, the system enables ships to be built with the minimum of skilled labour. These considerations will continue to have weight when normal conditions return, and so there is a very promising future for the concrete ship industry.

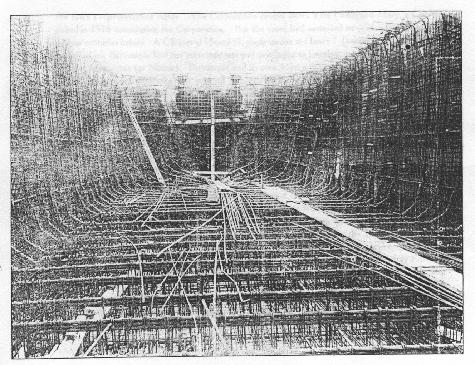

The deadweight capacity of the first Concrete barge constructed in Barnstaple – the one to be launched September 21st – is 1,000 tons. The length between the perpendiculars is 180 feet; beam at load line 31 feet; moulded depth 19 feet. The interior arrangement is that laid down in the Admiralty specifications, the three holds being separated by transverse bulkheads, and the spaces fore and aft providing accommodation for the captain, mate and men, as well as for a steam boiler, coal bunkers, store and equipment generally. The concrete of the hull of the ship is 3½ inches in thickness. One of the illustrations in this souvenir shows the framework of iron which is erected before the concrete is put into place, wooden casings being used to mould the concrete to the required lines. The 90 feet tower (constructed of timber) gives a fall sufficient to distribute the concrete on several slips.

A View of the Interior of the Ship showing the Steel Work

There is a set of offices contiguous to the yard, but the main offices are located in the commodious premises, known for several generations as The Golden Lion Hotel. This building is one of the most interesting survivals of old-time domestic architecture in Barnstaple, and is famous for its wonderful plaster ceilings. In 1732 it was described as the only house outside the South Gate of the town. It was orginally the town house of the Earls of Bath, and the arms of that noble house figure in the unique plaster work of the ancient banqueting room which is to-day the private office of Mr. Percy Westacott. Appropriately enough, a spirited representation of a ship in full sail figures in that coat of arms – a passive link between the glories of a long-distant past in the history of Barum and the hopes of a present that is rich in promise for the ancient borough of Barnstaple.

W.F. GARDINER.

The name of this ship is believed to be the Cretepath and she grounded on a sandbank after the launch and broke her back. An inauspicious start for the company and, after building and successfully launching a replacement the following year, they were reconstituted to make steel coasters. There is no longer any trace of the company.

As mentioned in the booklet, a large number of these ships were built throughout Europe and in the USA. Very few still survive. Here is an article in Wikipedia which gives some more background.

There is also a new website The Crete Fleet which has compiled an account of the surviving ships and some of those no longer with us.